Portraiture has always been about how we frame the world. What gets left out or blurred out, and who gets left out - that matters. It matters everywhere.

But in a city where every 90 percent of the gold-framed paintings feature a side-burned white guy on a horse, putting someone else in the picture is important.

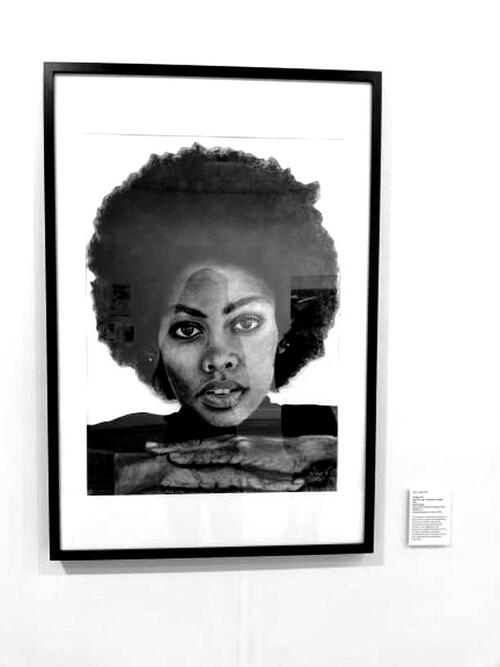

23-year-old artist Abbie Leigh Phillip leaves blackness in the frame in a way that history too often chose not to.

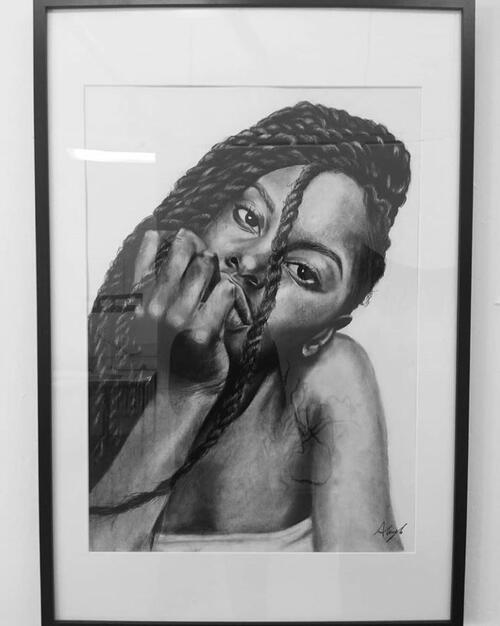

Her show at The Courtyard is a study in beauty, but through a kind of everyday blackness that comes in part from the everyday nature of the relationship between black women and their black hair. The set of charcoal portraits fills the frame with both.

“They’re all of modern black women - one’s an actress, one’s a model, one’s a child from Namibia and one’s an Instagram influencer,” Abbie said. “I was looking at beauty ideals. How they are all seen as being beautiful *for black women*, but there’s still, always, that ideal of being Western.

“When I had done my first series of portraits, one of my tutors asked ‘would you be happy if someone saw those and just thought ‘look there’s some fit black women on the wall?’ – to challenge me.

“And obviously I wouldn’t. That’s not what it’s meant to be about. I care what people take from it. I like the element of narrative through a series of portraits. It brings a sense in this, that these women are united by something.”

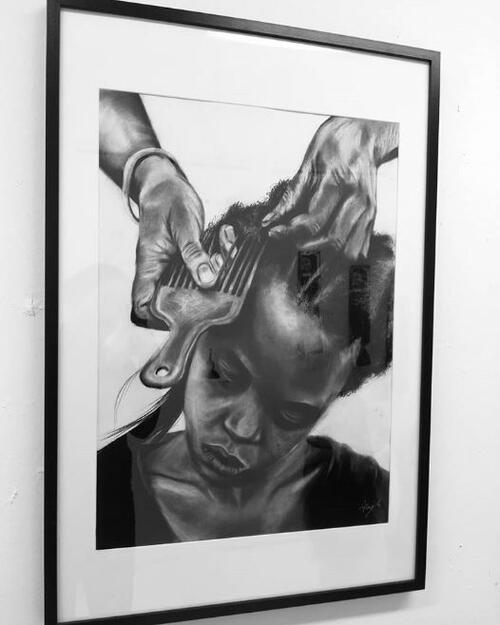

There’s this link between hair and community and identity that’s wrapped up in black culture in a way that’s both individual and universal, and also complicated. Abbie herself is half-Trinidadian. She tells me that initially hair straightening wasn’t to do with wanting to be more white, it was a way of connecting – and a rite of passage to adulthood. You would have braids as a kid and then straighten your hair as an adult.

“Braid’”, she added. “also means happiness in Bantu.”

Unfortunately the complex geopolitics of a world of Cancel Culture and facetuned selfies and a historically white filter over everything mean that if you’re black woman, even what grows out your head counts as a political statement in 2019. Too often it isn’t one that means happiness.

“Afro hair itself represents blackness. Personally, when I wear it natural it’s hard to comb. But when I go to places like London, they make the assumption that you don’t like who you are if you put on a wig or wear straight hair.

“In a way, I’m glad I’ve grown up in a not very diverse place. People tend to – rather than being horrible – they just tend to be overly nice. ‘I love black people’ that kind of thing. I don’t mind that. That’s fine. Do that if you want.”

This particular series of portraits was first displayed alongside a pair of installations, both made using hair (“and a lampstand”). Some of the hair was bought, some of it was Abbie’s. And the simpler piece of the two was a well-used afro comb titled Daily Struggle.

“The middle portrait, that one of the child? That got me thinking about my own childhood and how I had to deal with my hair, and my Mum combing it for hours.

“I’ve always lived in a place that’s not diverse. My mum lived in a village near Wrexham. There were cows in the field next door.

“I was the tallest person in the school as well for a while. I grew up really quick. I was taller than my twin brother. And I used to get comments. When I was a kid, I used to hate being black. Hate it.”

If that’s long-since faded (“although I’m glad I’m not a teen now, with social media influencing how you should look”), you can talk with Abbie for five minutes about everything from the prohibitive cost of rural haircare to fearful taxi rides with unintentional-or-maybe-not-that-unintentional racist cabbies before getting a sense of the exhaustive nature that everyday blackness comes with – and just why it’s so important that we see those faces and hear the depth of those stories in art and film and on the ‘gram.

It’s in part what drew her to portraiture as style.

“We look at people every single day,” she said

“I get asked a lot why I don’t do photography. But I don’t want my work to be photo-realism. I want it to represent the image.

“If you’re drawing, you can trace that person’s face – you’ve looked at their face for so much longer than a photograph. I find it more interesting. You can tell something different from a drawn portrait than you would from a photograph.”

And Abbie goes at it with an almost monastic dedication. She’ll try and finish the portrait in two sittings – one if she can manage it – with no music, and often starting in the evening and working through the night.

“I need to be able to be on my own to focus. It’s great, apart from seeing no natural daylight.

“I tend to forget to eat and drink and just work. I can’t leave my work and come back to it more than a couple of times. I start seeing the faults and just get rid of it.”

It’s working. She’s had recent shows at Canwood where one of here more “gestural”, abstract portraits sold - while a few others warped in the barn – and a recent exhibition at the Cider Barn in Presteigne.

“I felt that people there were interested in it because it was different. A lot of the rest of the work there was animal portraits. And landscapes. They are nice.”

The show at the Courtyard, which runs from today until Saturday April 13, coincides with Woke, a celebrated drama about Black Panthers and civil rights that hits the stage there on Monday night.

Go check out both – and follow Abbie on Instagram to see more of her work.