James Gardner was back in Hereford to introduce his first feature at Borderlines Film Festival.

“I used to work here actually. In the kitchen, making sandwiches on the weekend.” The Jellyfish director turned in his seat to look around the Courtyard restaurant. “It’s changed a bit though. It wasn’t, this back then.”

His film is a story of heart and hardship and has, what my boss called, “more than a bit of Ken Loach about it”. It’s set in south coast Kent, around a seaside town that was forced to watch its past glories fade and its arcades rust in the sea air as people headed to the Costa Del Something for their holidays, and locals looked inland for work. At the middle of all that is Liv Hill trying her heartbreaking best to laugh her way through a crisis in young caring.

Gardner wrote Jellyfish. He shot it, and he produced it. His camera captures that world and those left there with a kind eye. But the film has fingerprints everywhere of a director who knows what it’s like to grow up in a small town that people look to leave.

“This idea came from wanting to tell a story of this teenage girl who lived in Margate and discovered this talent and how her familial circumstances threatened to suffocate and stifle that.

“I love Margate. I’ve been going up and down from there for about 15 years.

“I don’t want people to see Jellyfish and see it as an indictment on Margate. Because it’s not. Sarah’s circumstances aren’t unique to Margate. There’s multiple Sarah Taylors in Hereford. And in Ross. And in Mordiford.

“Maybe that’s where it came from.”

From red carpets in Rome to brunch with DeNiro at Tribeca Film Festival in New York, the Jellyfish team has taken on brighter lights and Breakfast Shows over the last 12 months. Gardener has cast ex-Libertines in past projects and talks as easily and intensely about film and Fellini, and about his own projects, as any director you’ll hear from. But as his Borderlines Q + A approaches, there’s a slight edge in his voice.

There is a special pressure that comes with a hometown screening.

“I know there's going to be people I know when I get in there,” he said, having decided against sitting through another screening for a film he first drafted in 2015 and has toured on the festival circuit for more than a year.

“It’s not hard to watch it, but you see everything, every frame, every deliberate decision you made. Like brushstrokes on a painting. And I’ve seen it so many times.”

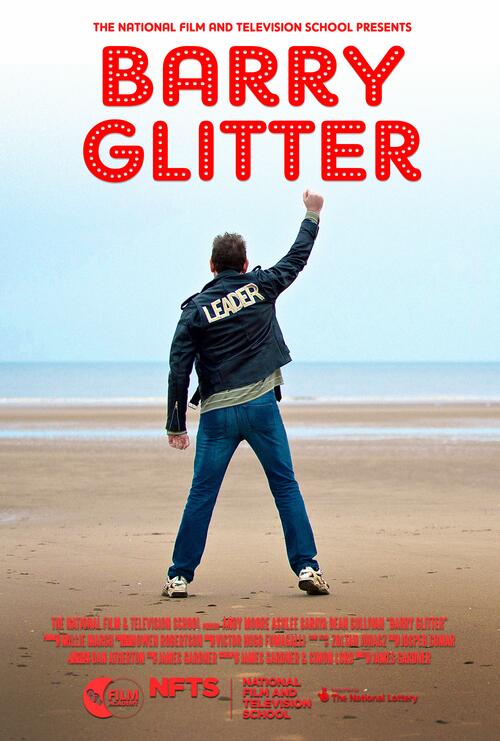

Both while at and since graduating the National Film & Television School, Gardner made a number short films.

Among them was a brilliant and, at times, bloody Northern drama about a Gary Glitter tribute act continuing to perform after his idol hits the front pages, an idea he’s since returned to.

His first short, Two Dancers, was an investigation in marriage and intimacy and ballet that starred ex-Libs’ Carl Barat and that “you will probably will never see”. But for the ex-HCA pupil, this wasthe first time many in the sold-out audience - aunts, uncles, maybe an old BHBS drama teacher who lent his name to one of Jellyfish’s characters - would see his work and his name on a big screen.

Across the Courtyard lobby, and starting 15 minutes before Jellyfish, was a screening of Mid90s, Jonah Hill’s directorial debut, a love-letter to a Blockbuster Video-era skateboarding, and to his own youth spent hanging out in car parks. It's a nice coincidence.

Life, aching limbs, and the endless schedule of promoting and producing an independent film have meant Gardner doesn’t really skate any more. Although he could, and did, well past his 30th birthday and through bad knees and battle-scarred shins.

But before he was on red carpets, the director was a minor celebrity of every Hereford retail park, every county quarter pipe, as a skater. Signed as a pro by the shoe company Vans, he was also behind a series of skate vids that for the first time really put Hereford spots on film.

“Skating in Hereford was good. It was limited, but there enough. -ish,” he said.

“But the fact that there’s not that much gives you the desire to go out.

“That’s how I started filming actually. And you become so obsessive with it, you don’t really realise you’re doing it. You’re mucking around. It’s great. You just make loads of mistakes. You figure out how to do things, to use editing software, tempo, shooting, how to put music on. I learnt a hell of a lot.

“And when you’re a skateboarder, it informs you culturally so much with the art and music. Skateboarding is so omnipresent in culture, and we don’t really realise it, from directors to artists like Keith Haring.”

Like the Courtyard, the skate scene in Hereford has changed a bit since then. But before was a shiny new park on Holmer Road (“I actually prefer the one in Newton Farm, it’s smaller, which is better for me these days”), there was The Red Rail At B&Q and The Aldi Gap and begging your way to Ross-on-Wye to drop in on a burning hot metal ramp.

Gardner was the first person to catch all that on tape. You could feel the fun and frustration and the loose gravel on every grainy landing of his Malajusted films. If you talk to people like Lewis Royden, who filmed and produced the Hereford-centric Wizards of Radical film last year, they know those videos. If you talk to people like local AMFAS skater Mike Gribben, they’ve heard the stories about that scene, and the old days.

It was through skating that Gardner first went to Margate. His sponsor lived there, and he used to go down to visit, to pick up new decks and free shirts. It’s was on those trips that he first got a feel for the place he’d film his debut feature ten years’ on, for the first time co-ordinating every movement of a feature-sized crew, bringing in to existence every frame of a script he wrote every word of.

“The shoot was three six day weeks. That’s the legal limit – you have to take one day off a week,” he said.

“I was living there for a month before and a month after. It was so hard because it was so personal. Everyone who worked on the film did it for deferred payment. Nobody was getting paid unless the film generates revenue.

“To go in to the psychology of why people make films. That’s a black hole.

“Every point of the film-making process, things get narrowed down until eventually you end up with the final film. When you’re sat in front of a blank page, the possibilities are limitless. When you get on the set they become a lot narrower, then you get in to the edit and they’re narrower still.

“The difference between a blue shirt and red shire is huge.

“As a director, it’s not a given that your costume designer knows what you’re thinking and understands why you want a blue shirt and not a red one. When it’s up on a cinema screen, that shirt, that difference, it’s huge.

“As a director, your job is communicate in such an effective way so that everyone on set knows exactly what they’re doing.”

Now based in London, he still comes back, every few months, to Hereford to see his family. And for the “virtues of space, good roasts … and Butty Bach.”

There’s real affection with the way he talks about the area. But also a thinly-veiled frustration that like Blackpool and Margate and some of the towns he’s filmed in that have been left behind, there is much about Hereford that hasn’t moved as quickly as the Courtyard – and that means it is still a place where creative people, and young creative people, will look to leave and come back to.